Ever notice that your bacterial vaginosis symptoms seem to get worse after sex or during certain times of your cycle? You’re not imagining it. BV symptoms can definitely flare up in response to changes in your vaginal environment. The culprits often involve sex, shifts in pH levels, and disturbances in the delicate vaginal microbiome. Let’s unpack why this happens and what it means for managing BV.

The Role of pH: Why Sex Can Trigger BV Symptoms

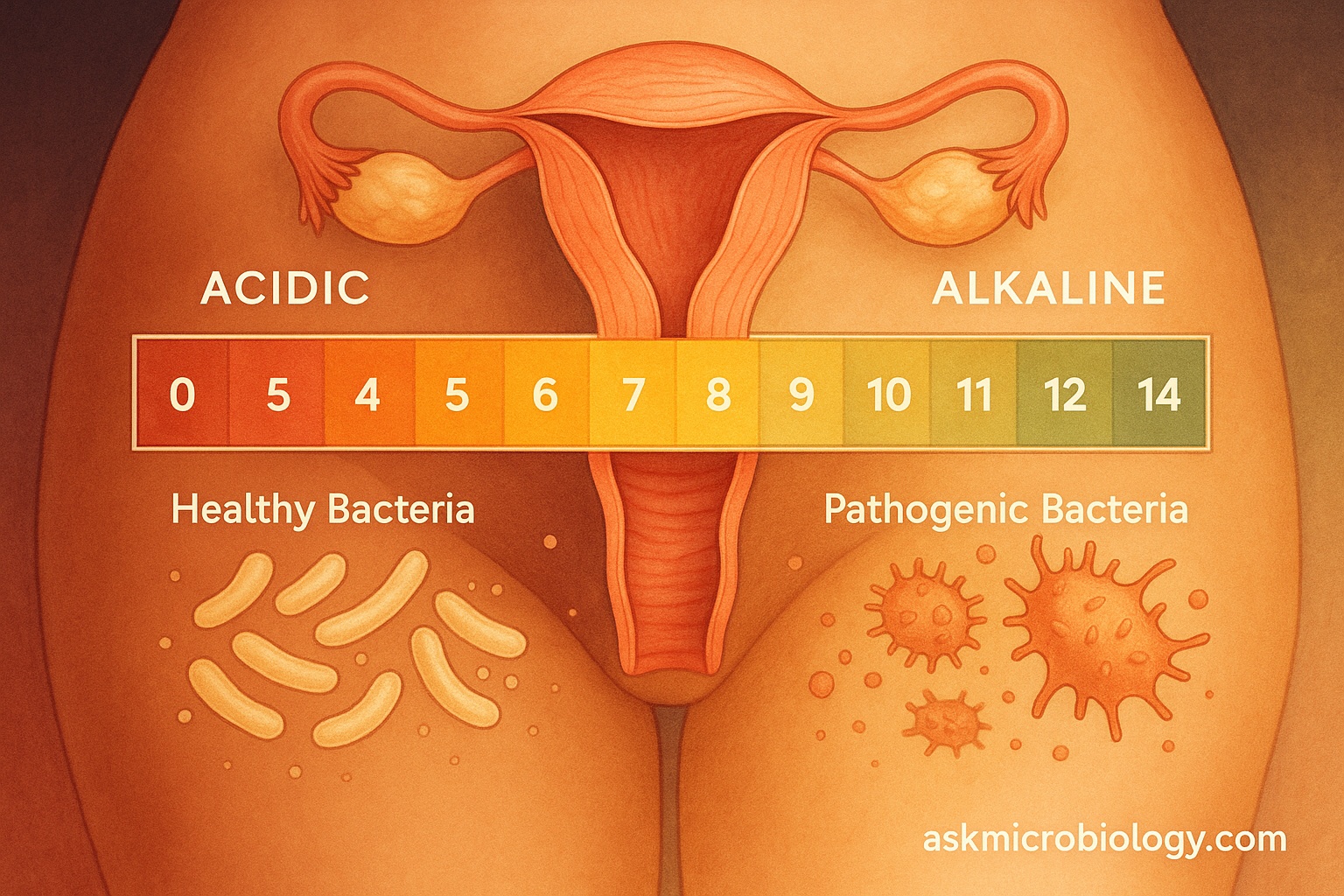

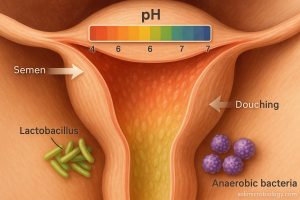

A healthy vagina is slightly acidic, usually with a pH around 3.8 to 4.5. This acidity is maintained by beneficial bacteria (primarily lactobacilli) that produce lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide. These good bacteria keep the vaginal ecosystem balanced and hostile to harmful microbes.

Enter sex: Semen is alkaline, with a pH often between 7 and 8. When semen enters the vagina, it can temporarily raise the vaginal pH. This isn’t usually a problem in someone with a well-balanced vaginal flora – the lactobacilli will typically restore the normal acidity over time. But if you have BV or are prone to it, that rise in pH can spell trouble: – Fishy odor intensifies: One hallmark of BV is the fishy odor, caused by compounds called amines that BV-related bacteria produce. These amines are much more noticeable in a higher-pH (less acidic) environment. That’s why many women notice the odor becomes very strong right after unprotected sex. The alkaline semen essentially “activates” the odor. (Fun fact: Doctors use a similar effect in the lab – the “whiff test” – by adding a drop of alkaline solution to a BV sample to see if a fishy smell is released.) – Upsetting the balance: If your lactobacilli were already struggling, an infusion of semen’s alkalinity can knock them down even further, allowing the BV-associated bacteria to flourish. Women often report that their BV comes back after sex with a new partner or after sex without a condom. It’s not that BV is exactly an STI, but sex can change your vaginal flora. Unfamiliar bacteria from your partner, or just the pH change, can tip the scales in favor of BV microbes.

It’s important to note that sexual activity can trigger BV symptoms even if no semen is involved. Oral sex, for example, introduces different bacteria and has its own pH (saliva is also neutral to slightly alkaline). Some women also find that sex toys or lubricants disrupt their vagina’s normal environment, especially if those toys weren’t properly cleaned or if the lube has ingredients that alter pH. And interestingly, women who have sex with women can pass vaginal bacteria back and forth; having a female partner has been associated with a higher risk of BV, likely because of this sharing of flora.

Using condoms can help in some of these scenarios. Condoms prevent semen from affecting vaginal pH, and they can somewhat shield the exchange of bacteria. In fact, not using condoms has been identified as a risk factor for BV (because the vagina is more frequently exposed to semen and new bacteria). This is why if you keep getting BV, one of the lifestyle tweaks a doctor might suggest is using condoms more regularly.

Other Triggers That Disturb the Microbiome

Beyond sex, there are several common triggers that can make BV symptoms flare or increase the risk of a BV episode. Most of them have one thing in common: they disrupt the normal bacterial balance or pH of the vagina.

Menstrual cycle: Right before and during your period, vaginal pH rises (menstrual blood is relatively alkaline). It’s not unusual for women to notice BV symptoms either during their period or just after it. You might experience a stronger odor or unusual discharge at the end of your period. For some, BV actually tends to recur right after menstruation. The blood’s higher pH and the temporary dip in lactobacilli during menses can create a window where BV bacteria overgrow.

Douching and over-cleaning: The vagina is self-cleaning. When you douche or use vaginal cleansers, you might think you’re being extra fresh, but you’re likely doing more harm. Douching can flush out the protective lactobacilli and actually raise vaginal pH (most douching solutions are not appropriately acidic). Studies have repeatedly shown a link between douching and BV. Similarly, using harsh or perfumed soaps in the vulvar area can irritate tissues and disturb the natural flora. The same goes for vaginal deodorants or scented tampons – they might smell nice, but they can upset your vagina’s normal chemistry.

Antibiotics (and other medications): Antibiotics you take for, say, a sinus infection or acne don’t target only a specific body part – they circulate everywhere, including to the vagina. They can kill off good bacteria along with the bad. Many women notice yeast infections after antibiotics; BV can also occur or recur post-antibiotic because the lactobacilli get wiped out. Some research also suggests that high-dose steroids or other medications that affect your immune system might make BV more likely, since your body’s usual bacterial control mechanisms are altered.

Hormonal changes: Apart from periods, other hormonal shifts can influence vaginal flora. Pregnancy, for example, changes the vaginal environment (interestingly, some women get BV for the first time in pregnancy, while others who have chronic BV see it go away during pregnancy). Menopause, which leads to lower estrogen and less glycogen in vaginal tissues, often results in fewer lactobacilli – some older women get a BV-like vaginitis due to this change. Even stress or lack of sleep might indirectly affect your immune system and hormones enough to give an edge to BV bacteria (there’s some evidence that high stress levels are associated with BV).

Diet and lifestyle: What you eat might affect your vaginal microbiome subtly. A diet high in sugar can possibly encourage yeast infections more than BV, but generally, a balanced diet supports your immune system and overall microbial health. There’s some observational data that women with BV are more likely to smoke cigarettes. Smoking could be a marker of other behaviors, or it could have a direct effect (some studies suggest it might reduce cervical immune defenses). Either way, lifestyle factors like smoking, poor diet, or lack of sleep might set the stage for infections by weakening your body’s normal defenses.

Clothing and sweat: Believe it or not, your fashion choices can play a minor role. Tight, non-breathable clothing (think nylon underwear or yoga pants 24/7) can create a warm, moist environment around your vulva. Why does this matter? BV-causing bacteria are anaerobic, meaning they thrive in low-oxygen environments. While it’s not the biggest factor, staying in sweaty gym clothes or always wearing non-breathable undies can contribute to general vaginal irritation or microbial imbalance. It’s a good practice to change out of wet or sweaty clothes promptly and opt for cotton underwear to allow some airflow.

Lubricants and products: Some sexual lubricants, especially those with glycerin or warming agent

s, can mess with pH or cause irritation that gives bad bacteria an opportunity. Oils and petroleum jellies used internally can also alter the environment. If you’re prone to BV, using a pH-balanced, water-based lubricant without fragrances or sugars is usually best.

Managing and Preventing BV Flares

Knowing these triggers is half the battle. While you can’t control everything (you shouldn’t stop having sex or menstruating, obviously!), you can make small adjustments: Use protection: If BV flares after unprotected sex, consider using condoms more often. It can help minimize pH disruption from semen and reduce the influx of new bacteria. Skip the douching: Trust your vagina’s self-cleansing ability. Cleaning the outside with mild soap is fine, but don’t flush the inside. If you feel the need for extra freshness, talk to a healthcare provider – recurrent BV might be the real issue, not your hygiene routine. Post-period care: Some women use hydrogen peroxide-based gels or probiotic suppositories right after their period to help restore acidity. Talk to your doctor before trying these, but be aware that the post-period BV flare is a known phenomenon. In some cases, a doctor might suggest a preventative measure, like using a prescribed vaginal gel (metronidazole or an acidic gel) for a couple of days after your period to ward off BV. Lifestyle tweaks: Wearing cotton underwear, avoiding sitting around in damp clothes (like a wet swimsuit or sweaty gym pants), and quitting smoking if you smoke – these can all contribute to a healthier vaginal environment. A generally healthy lifestyle (balanced diet, regular exercise, stress reduction) supports your immune system, which in turn helps keep your vaginal bacteria in check. Communicate with partners: If you have a steady partner, it can help to let them know that you’re dealing with BV. Sometimes both partners may need to pay attention to hygiene (for example, ensuring hands or sex toys are clean, or using condoms). While treating a male partner with antibiotics isn’t standard for BV, it’s still worth discussing sexual health openly. If you have female partners, it’s good for both of you to be aware that sharing vaginal fluids could swap bacteria – so hygiene and possibly simultaneous treatment might be considerations.

Above all, remember that BV is very common and nothing to be ashamed of. If your symptoms flare up, it doesn’t mean you did something “wrong” – it’s often a quirk of biology. By understanding the t

riggers, you can anticipate when you might need to be extra-vigilant (like around the time of your period or after having a new sexual partner). And if you do get a flare, you’ll recognize it quickly and can seek treatment promptly.

References

- https://utswmed.org/medblog/bacterial-vaginosis/

- https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/6-contributors-to-bacterial-vaginosis

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/3963-bacterial-vaginosis

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/254342-overview