In the food industry, a single microscopic organism can spell disaster. We’ve all seen headlines like “Massive recall of ground beef due to E. coli” or “Listeria outbreak prompts deli meat recall.” For restaurants, manufacturers, and farms, certain bacteria are the ultimate villains – they can make customers seriously ill, trigger costly recalls, and damage a company’s reputation overnight. So, which bacteria cause the greatest harm in the food industry? Here we’ll count down eight of the most harmful bacterial culprits when it comes to foodborne illness and contamination, and discuss how each can be controlled. These “Top 8” are responsible for a huge portion of food poisoning cases and outbreaks worldwide.

By understanding these bad bugs, food professionals and consumers alike can better appreciate why safety rules are in place (like cooking temperatures and sanitation protocols) and how following them keeps us safe. Let’s dive into the list, starting with the heavy hitters like Salmonella, and working through other major pathogens that keep the industry on its toes.

1. Salmonella

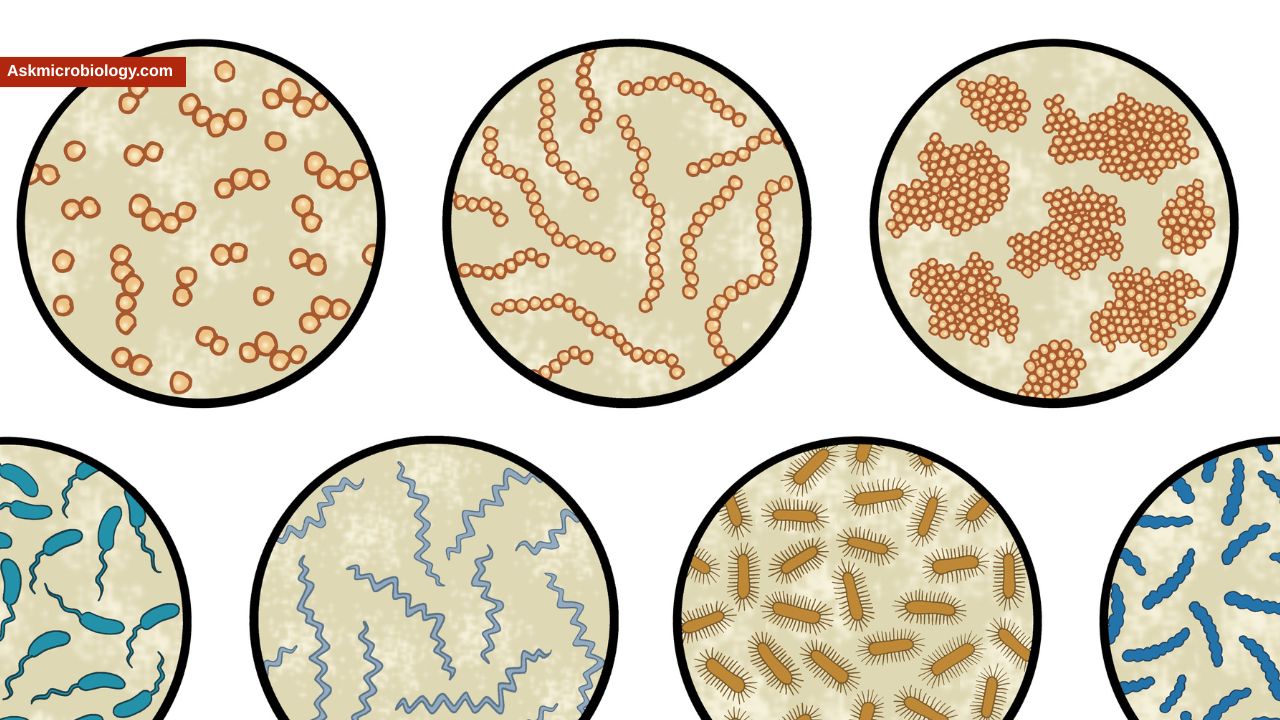

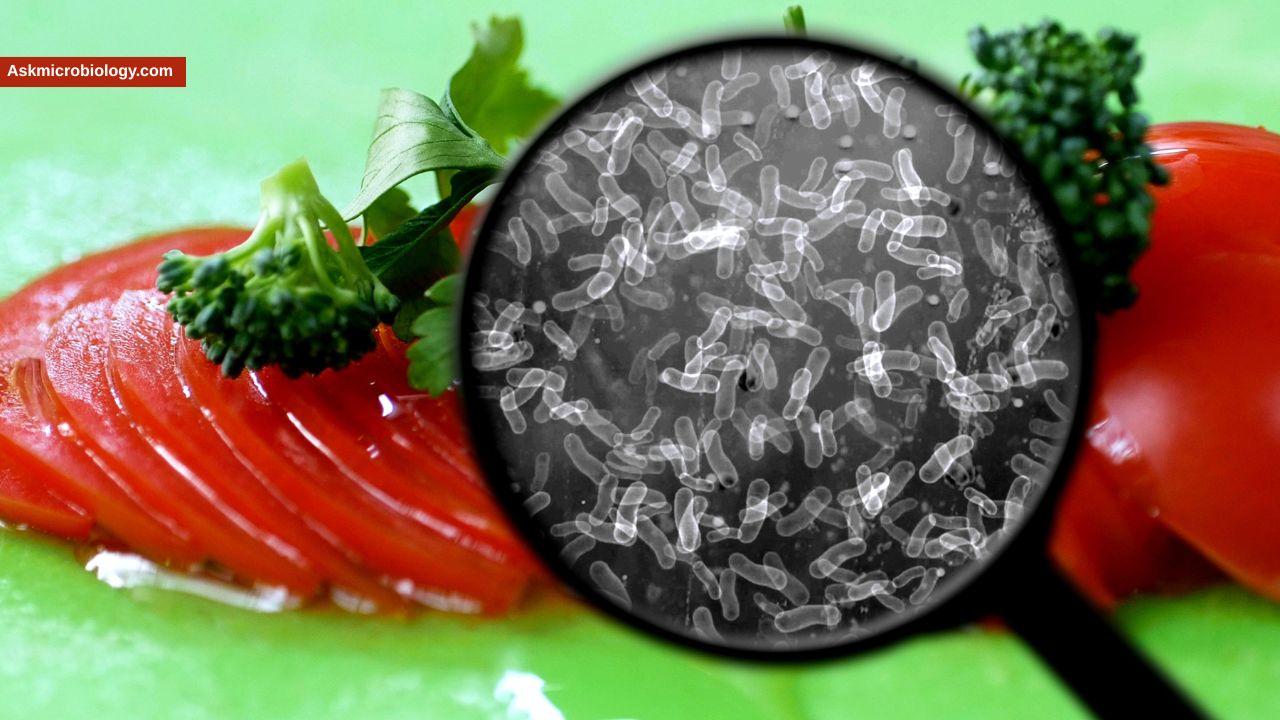

Why it’s harmful: Salmonella is often considered Public Enemy #1 in food processing and food service. It is extremely widespread – found in the intestines of birds, reptiles, mammals – and easily contaminates foods from farm to fork. Salmonella causes an illness called salmonellosis, typically characterized by fever, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps. While many cases are self-limiting, severe infections can occur, especially in young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised people. In terms of impact, Salmonella is a leading cause of foodborne illness globally. In the U.S. alone, it’s estimated to cause around 1.35 million illnesses and is the leading cause of hospitalizations and deaths from food poisoning. It’s a big reason we warn against raw eggs (due to Salmonella Enteritidis inside eggs) and undercooked poultry. Beyond human health, a Salmonella recall can cost companies millions and shatter consumer trust – just ask peanut butter producers who’ve had huge recalls after Salmonella was found.

Common sources: Undercooked poultry, eggs, raw milk, meat, and even produce like tomatoes, leafy greens, or sprouts (often via contaminated water or cross-contamination). Salmonella can also be a pest in dry products like spices or peanut butter – it’s hardy and can survive in dry environments for weeks.

Control measures:

– Cooking: Thorough cooking is highly effective. Heat kills Salmonella, so cooking chicken to 165°F, eggs until yolks are firm, etc., eliminates the bacteria. – Avoid cross-contamination: Prevent raw poultry or meat juices from contacting ready-to-eat foods. In processing plants, strict separation of raw and cooked product areas is crucial. At home, use separate cutting boards for raw meat and wash hands and utensils after touching raw items. – Chilling: Keep foods refrigerated. Salmonella won’t multiply at typical fridge temps. Also, avoid the danger zone – don’t leave prepared foods out warm for over 2 hours. – Sanitation: In factories, equipment must be cleaned and sanitized regularly. Salmonella can hide in equipment or facility environments (it has caused persistent contamination in peanut factories, for example). Facilities often test the environment for Salmonella to catch it early. – Purchase pasteurized eggs and milk: This reduces risk for foods that might not be cooked thoroughly (like sauces, dressings, or milk-based drinks). – Employee hygiene: Food handlers can spread Salmonella if they’re carrying it (some people can be asymptomatic carriers). Proper handwashing and glove use when appropriate help prevent human-to-food contamination.

2. Campylobacter

Why it’s harmful: Campylobacter (especially C. jejuni) is a leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide, often even more common than Salmonella in terms of causing diarrheal illness. It typically causes fever, cramping, and often bloody diarrhea. Most people recover in a week, but it’s miserable, and in rare instances it can lead to complications like Guillain-Barré syndrome (a serious nerve condition). For the food industry, Campylobacter is challenging because it’s extremely prevalent in poultry flocks – most chickens have some Campylobacter in their intestines. It doesn’t take much of it to cause illness (a few hundred cells can be enough), which means even a small bit of undercooked chicken juice can infect someone.

Common sources: Poultry is number one. Eating undercooked chicken or handling it and cross-contaminating other foods are typical routes. Unpasteurized milk and untreated water have also been sources, since cows can shed Campylobacter in milk and wild birds or farm runoff can contaminate water.

Control measures:

– Cook poultry properly: The single biggest preventive step is cooking chicken, turkey, etc. to 165°F internal temperature to kill Campylobacter. Color isn’t a reliable indicator – use a thermometer or ensure juices run clear and no pink meat. – Prevent cross-contamination: Because raw poultry is often carrying Campylobacter, treat it carefully. Use separate cutting boards/knives for raw chicken and wash them thoroughly with hot soapy water (or in a dishwasher) after use. Wash your hands after handling raw meat. In processing plants, interventions like chilling carcasses, using antimicrobial rinses, or air chilling can reduce bacterial loads. – Sanitize surfaces: In restaurants or home kitchens, cleaning and sanitizing anything that contacted raw poultry (counters, sinks, utensils) helps, because Campylobacter can linger for a short while. It’s somewhat fragile in air – for instance, it’s noted to survive up to 4 hours on surfaces – but you don’t want to give it even that chance. – Use pasteurized dairy: If you drink raw milk, you run a risk of Campylobacter (among other germs). Pasteurization kills it. – Water treatment: Municipal water is treated to kill Campylobacter, but if you’re camping or using well water near farms, using proper water treatment or boiling is wise.

3. E. coli O157:H7 (and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli)

Why it’s harmful: Escherichia coli is a huge group of bacteria; most strains are harmless, but the Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) are dangerous. The poster child is E. coli O157:H7, which can cause severe bloody diarrhea and can lead to Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) – a life-threatening kidney failure complication, especially in children. The case that put O157 on the map was the 1993 Jack in the Box fast-food outbreak, but since then, we’ve seen it in everything from spinach and lettuce to unpasteurized apple cider and fairgrounds (via animal contact). The harm comes not just from individual illness but also from the scope of outbreaks – produce contamination can affect thousands of packages across many states. For food businesses, an E. coli outbreak is devastating and leads to lawsuits, massive recalls, and public fear (for example, the romaine lettuce E. coli outbreaks in recent years caused nationwide salad greens advisories).

Common sources: Historically, undercooked ground beef was common (cattle are the reservoir; O157 can live in cow intestines and manure). But now we also see it in fresh produce (leafy greens, sprouts), often due to fields contaminated with animal feces or irrigation water. Unpasteurized juices or dairy can carry it. Petting zoos or farms can transmit it if people touch animals or manure and then eat without proper handwashing.

Control measures:

– Cook ground beef thoroughly: The USDA says at least 160°F for ground meats. Unlike a steak (where bacteria are mostly on the surface), ground meat mixes any bacteria throughout, so the interior must get hot enough to kill germs. – Avoid raw milk/cider: Use pasteurized products to kill any potential E. coli. Similarly, wash fruits before juicing them. – Produce safety on farms: This is a big one – preventing contamination of irrigation water with manure, keeping wildlife out of produce fields as much as possible, and following Good Agricultural Practices. Many farms test water and compost for E. coli. – Wash produce & kitchen hygiene: Thoroughly rinse raw fruits and veggies. It might not remove all microbes (especially if they stick strongly to leaves or biofilms), but it reduces numbers. In the kitchen, prevent cross-contamination: don’t let raw meat juices drip onto salad ingredients, etc. Wash hands after handling raw meat or after using the restroom – remember, one route E. coli spreads is person-to-person when hygiene is poor (it only takes a tiny amount of fecal matter with E. coli to infect someone). – Testing and inspection: The beef industry, for example, routinely tests ground beef lots for O157 and other STEC. Any positive leads to discarding the product. The FDA has regulations for juice (like the HACCP for juice requires treatment to achieve a certain bacterial kill). – Exclude sick workers: If someone has diarrhea, especially bloody diarrhea, they should not be preparing food for others. There have been cases of outbreaks from infected food handlers, although it’s more common with Norovirus or Shigella than E. coli. Still, it’s a precaution since any fecal-oral pathogen can be transmitted by a sick worker.

4. Listeria monocytogenes

Why it’s harmful: Listeria is a bane of the ready-to-eat food industry. It causes relatively few illnesses compared to the likes of Salmonella, but the consequences are severe. Listeriosis (the illness from Listeria) can result in miscarriage or stillbirth in pregnant women, and fatal bloodstream or brain infections in older or immunocompromised individuals. In the U.S., only around 1,600 cases occur per year, but about 260 of those people die – a very high fatality rate, around 15-20%. In fact, invasive Listeria infections have a mortality rate of 20-30%. It’s considered one of the most deadly foodborne pathogens per case. Listeria is also notorious because it can persist in food manufacturing environments and grow at refrigerator temperatures. It has caused a number of large recalls in products like deli meats, soft cheeses, frozen vegetables, and even ice cream. For any company producing foods that are meant to be eaten without further cooking (cold smoked fish, packaged salads, deli products, etc.), Listeria is top-of-mind as a hazard.

Common sources: Ready-to-eat deli meats and hot dogs, if contaminated after cooking; soft cheeses (especially those made with unpasteurized milk, like certain fetas or quesos frescos); pâtés or meat spreads; smoked seafood; and raw sprouts. Also, produce like cantaloupe or celery have been vehicles in big outbreaks (Listeria in soil or facilities can contaminate them). We’ve even seen Listeria in ice cream and frozen foods due to issues in processing plants. It’s widespread in the environment (soil, water) and can get into processing areas via shoes, equipment, or ingredients.

Control measures:

– Environment sanitation: Food plants must aggressively clean and sanitize, especially drains, coolers, and equipment. Listeria can form biofilms and lurk in nooks. There’s a practice of environmental monitoring – swabbing surfaces in the plant to detect Listeria – so that any positive can trigger sanitation actions. Some facilities use measures like UV lights or specific sanitizers effective against Listeria. – Temperature control: While Listeria can grow in the fridge, it grows slowly. Keeping food at 40°F or below and respecting shelf lives helps minimize its growth. – Pasteurization: Using pasteurized milk for cheeses and dairy prevents introducing Listeria at the start. For deli meats and hot dogs, processors often have a post-packaging pasteurization step or add surface antimicrobial sprays to kill any Listeria that might get on after cooking. – Segregation: In facilities, raw ingredients and RTE (ready-to-eat) products are separated so raw Listeria from, say, produce or soil doesn’t cross into the area where cooked products are handled. Workers might have color-coded uniforms or tools for different zones. – Consumer guidelines: High-risk individuals (pregnant, elderly, immune-weakened) are advised to heat deli meats until steaming and avoid high-risk foods like raw sprouts, unpasteurized cheeses, or refrigerated smoked seafood. This is because even with industry controls, a tiny Listeria presence can grow over time in the fridge. – Short shelf-life for RTE foods: Companies may set use-by dates to ensure that even if a bit of Listeria is present, it won’t have time to reach dangerous levels before the product is consumed. – Zero tolerance: Regulators have a zero-tolerance policy for Listeria in ready-to-eat foods (in many countries including the U.S.). This means if even one cell is found in a 25-gram sample of a ready-to-eat food, it’s considered adulterated. This strict standard pushes companies to maintain vigilant controls.

5. Clostridium perfringens

Why it’s harmful: C. perfringens doesn’t usually get front-page news, but it’s one of the most common causes of foodborne illness, often occurring in outbreaks at cafeterias, catered events, or holiday meals. It’s estimated to cause nearly 1 million illnesses in the U.S. annually, which shows how frequently it strikes. The illness is typically a toxicoinfection – you ingest a large number of bacteria in the food, then they produce toxin in your intestines that causes intense abdominal cramps and diarrhea. It’s usually not deadly (though it can be serious for very frail people), and symptoms tend to subside within a day or so. Because the symptoms often appear the day after the meal, C. perfringens outbreaks might be underreported (“24-hour flu” that was actually food poisoning). From an industry perspective, C. perfringens is a concern in food service and institutions. It grows rapidly in warm food; it can multiply to huge numbers in a dish that is cooling slowly on a steam table or sitting out too long.

Common sources: Foods that are cooked in bulk and then kept warm for a long time or cooled too slowly. Think large roasts, gravies, stews, chili, casseroles – especially in settings like school cafeterias, hospitals, prisons, or buffet restaurants. Meat and poultry are common ingredients in those dishes, and C. perfringens spores often exist in raw meat or spices. The spores survive cooking, and if the dish isn’t kept hot enough (>140°F) or cooled properly, the bacteria wake up and reproduce like crazy. By the time someone eats it, there may be millions of bacteria per bite.

Control measures:

– Proper hot holding: If food is cooked and meant to be served hot, it should be kept at 135-140°F or above until serving. For example, in a buffet line, use chafing dishes or steam tables that keep the temperature up. If hot food falls below that threshold for more than 2 hours, it’s safer to discard it. – Rapid cooling: If you have large volumes of food to cool (like a big pot of soup or a roast), use techniques to cool it faster. This can include dividing it into smaller shallower pans, using an ice water bath, stirring to release heat, etc. The goal is to get from hot to 70°F within 2 hours and from 70° to 40°F in another 4 hours (that’s a standard cooling guideline). The faster it goes through the 140-40°F range, the less chance C. perfringens (or others like B. cereus) have to grow. – Reheating to 165°F: When reheating leftovers, bring them up to a boil or 165°F throughout. This will kill active C. perfringens cells (though not spores). Importantly, note that reheating will not destroy any toxin that might have already been produced, but for C. perfringens, the toxin is made in the gut after ingestion, not pre-formed in the food, so reheating addresses the primary risk. – Timing: Don’t let foods sit out at room temp. Even during family dinners, it’s wise to pack up the leftovers within 2 hours of serving. In commercial kitchens, follow the “two-hour rule” for leaving cooked food out. – Adequate cooking: Ensure initial cooking reaches safe temperature; while C. perfringens spores survive, proper cooking will kill the active bacteria, so you start with a lower load that could grow if there’s a lapse in temperature control later. – Temperature monitoring: In institutions, staff should use thermometers to monitor holding units and the center of foods to ensure they stay in safe ranges.

6. Staphylococcus aureus

Why it’s harmful: Staphylococcus aureus causes a nasty form of food poisoning that hits quickly with severe nausea and vomiting. It’s not usually life-threatening, but it can knock you out for a day. Staph is a unique risk because it’s not the bacteria itself causing illness, but a heat-stable toxin it produces in food. This toxin can withstand cooking temperatures that would kill bacteria. So food could be contaminated, left unrefrigerated, toxin produced, and even if you heat it up later, the toxin remains to make you sick. For the food industry, Staph is a concern particularly in foods that are handled a lot by people (since it commonly lives on our skin, in cuts, in our noses) and then not cooked further. A classic scenario: a worker with a Staph infection on their hand handles cooked ham or a cream pastry; the food sits in the “danger zone” for several hours; Staph grows and makes toxin; people eat it and within hours are violently ill. Outbreaks have occurred in bakery items, deli salads, sliced meats, and sandwiches. It’s a reputational hit for any deli or restaurant because it implies poor temperature control or poor hygiene.

Common sources: Cooked meats (ham, chicken) that are later improperly stored, egg and potato salads, tuna salad, bakery products with cream or custard, sandwiches, and other ready-to-eat items that might sit out. Anywhere humans touch food a lot – catering lines, sandwich assembly – there’s a risk if someone carries Staph and food isn’t kept chilled. Also, raw milk or cheeses made improperly can have Staph, and if they allow growth, toxin can form (some outbreaks of staph toxin have been linked to cheese).

Control measures:

– Strict personal hygiene: Food handlers must wash hands thoroughly and wear gloves or use utensils, especially when handling ready-to-eat foods. Cover wounds – if someone has a hand infection or even a bandaged cut, ideally they shouldn’t be directly prepping foods. Staph often resides in the nose, so avoiding bare-hand contact (using gloves when appropriate) can minimize transfer from sneezes or touching one’s face. – Keep foods cold (or hot): After preparation, keep foods like salads, deli trays, or cream pastries refrigerated below 40°F until serving. If they’re out on a buffet, they should be on ice or replaced frequently (within 2 hours). Remember, Staph grows quickly at room temp and can produce toxin in a few hours. It does not compete well with other bacteria in raw foods, but in cooked, handled foods (where other bacteria might have been killed off), it can flourish without taste or smell changes. – Small batch preparation: In food service, it’s safer to make salads or sandwiches in small batches that will be used quickly, rather than huge batches that sit for a long time. – Rapid cooling of cooked food: If you cook a big roast or a batch of chicken and plan to use it cold (say for chicken salad), cool it quickly and then mix the salad and get it chilled. Don’t let the cooked meat sit out for hours while prepping other things. – Sanitation: Clean equipment and surfaces can help since Staph can be on food contact surfaces via human shedding. Regularly sanitize tools, cutting boards, slicers, etc., especially in deli areas. – Educate staff: Staff should be aware that coming to work ill (even with just a skin infection or if they had vomiting recently) can be problematic. Some jurisdictions have food safety rules requiring food workers to report illnesses and exclude themselves if they have symptoms. While that’s more targeted at things like Norovirus, any illness that could cause contamination should be considered. –

Testing in dairy: For dairy producers, testing milk for high Staph counts can prevent using it for cheeses where the toxin could form if not handled right. Pasteurization kills Staph bacteria, but if milk had a ton of Staph and wasn’t cooled, it might already have some toxin (though pasteurization might degrade some toxin, it’s not guaranteed if levels were high).

7. Clostridium botulinum

Why it’s harmful: C. botulinum is the bacterium behind botulism, a disease that, although rare, is extremely severe. The bacteria produce botulinum toxin, which causes paralysis; consuming even tiny amounts of this toxin in food can lead to respiratory failure and death if not treated. For the food industry, botulism is the nightmare scenario for canned and packaged foods because it’s often lethal and results in high-profile recalls and public fear. Historically, home canning has been a big source of botulism cases (people not using proper canning methods for low-acid foods). Commercially, botulism outbreaks have been very infrequent but have occurred (e.g., in improperly processed canned goods, vacuum-packed smoked fish held at room temp, or garlic-in-oil mixtures without acid). The organism’s spores are widespread in soil and marine sediments. They are harmless until they find an anaerobic, low-acid, room-temperature environment – then they can germinate and produce toxin.

Common sources: Improperly canned vegetables or meats, improperly processed low-acid canned foods (anything with pH > 4.6 that isn’t sufficiently heat processed to kill spores, like canned corn, peas, green beans, fish, etc.), homemade flavored oils (if herbs or garlic with spores are bottled anaerobically without acid and not refrigerated), lightly preserved fish (traditionally fermented or salted fish if not done right), and infant botulism from spores in honey. In industrial contexts, low-acid canned foods are done under very strict controls (FDA requires something called a “botulinum cook” of 121°C for a certain time in pressure canning to kill spores). Failures are rare but can be catastrophic.

Control measures:

– Acidity and formulation: Ensure products that are bottled or packaged anaerobically are sufficiently acidic (pH 4.6 or below) or have other hurdles like salt/sugar that prevent C. botulinum growth. For example, acidified foods (like pickles, hot sauce) must be verified to have low pH throughout. Garlic or herbs in oil should have added acid or be kept refrigerated. – Proper canning/retort processing: Commercial canneries use retorts (like big pressure cookers) to reach temperatures above boiling (like 250°F / 121°C) to kill C. botulinum spores. They also have can seam integrity checks and other quality control to ensure the can is sealed and processed correctly. Home canners are advised to use pressure canners for low-acid foods and follow tested recipes. – Refrigeration: Keep perishable infused oils or vacuum-packed foods in the fridge, which slows or stops C. botulinum. Many smoked fish products, for instance, are sold refrigerated and also have a short shelf life and sometimes salt or nitrites to inhibit botulinum. – Use of preservatives: Certain preservatives like nitrites in cured meats (e.g., some sausages, cured fish) were traditionally used in part to prevent botulism. Food scientists ensure that formulations for things like processed meats include inhibitors for C. botulinum. – Detection: Swollen or bulging cans, or foul odors (except in some botulism cases the food looks/smells normal) – when in doubt, “when it doubt, throw it out” for canned goods. The industry also does incubation tests on sample canned products (storing samples at elevated temperatures and checking for any swelling or toxin). – Education: A lot of prevention is at the consumer and artisan level – making sure people know not to improvise with canning times, to boil home-canned low-acid veggies for 10 minutes before tasting them (an old recommendation as an extra safety step), and so on. Many countries have outreach programs to educate about safe canning and preserving to prevent botulism.

Thankfully, botulism in regulated commercial products is exceedingly rare now, but it remains a top concern due to its severity. Every canning plant has C. botulinum control as its number one priority in low-acid canning operations.

8. Bacillus cereus

Why it’s harmful: Bacillus cereus is another spore-forming bacterium that causes food poisoning, though usually a relatively mild one. It’s known for causing two types of illness: an emetic (vomiting) syndrome and a diarrheal syndrome. The vomiting type often hits within a few hours of eating and is associated with a toxin produced in the food (similar to Staph toxin scenario), particularly in starchy foods like rice. The diarrheal type occurs more like 8-16 hours after eating and is due to a different toxin produced in your intestines, often after eating things like meats, soups, or vegetables that were left at warm temps and allowed B. cereus to grow. In the food industry, B. cereus is a concern for any cooked foods that are cooled slowly or held warm improperly, similar to C. perfringens. It’s also an occasional spoilage issue in pasteurized milk (the spores survive pasteurization and can germinate later). For consumers, the classic B. cereus story is “fried rice syndrome” – eating fried rice that was made from rice left out at room temp, leading to sudden vomiting.

Common sources: Cooked rice and pasta that have been left out or improperly cooled (the starch seems to bind the toxin, and outbreaks commonly involve fried rice from restaurants or buffets). Also, stews, casseroles, sauces, and dairy products that sit too long in the danger zone can grow B. cereus. Contaminated spices have occasionally been implicated because B. cereus is in soil and can be present in dried foods (though spices usually don’t have enough moisture for growth until they’re in a dish).

Control measures:

– Timely refrigeration of cooked grains: If you cook rice or pasta and are not eating it immediately, cool it down quickly. Spread it in a thin layer on a tray or put the container in an ice bath, then refrigerate. Do not leave cooked rice sitting out for hours. In restaurants, rice cookers often hold rice hot; the danger is when a big batch is cooked, left to cool at room temp, then later made into fried rice – instead, chill it fast. – Keep hot foods hot, cold foods cold: Same mantra – do not let prepared foods linger between 40°F and 140°F. B. cereus grows well at room temp and even up to warm temps (around 85-95°F is prime for it). – Small batches: Prepare foods in quantities that will be consumed or cooled quickly. For instance, in a buffet setting, better to replace trays more frequently than to have one massive tray sit out. – Reheat thoroughly: While the vomit toxin of B. cereus (cereulide) is heat-stable, the diarrheal toxin is not preformed in food – it’s made in the gut – so reheating food that has B. cereus growth can kill the bacteria and prevent further toxin formation. However, if rice already has cereulide toxin from B. cereus, no amount of frying will remove it – so it circles back to preventing the growth in the first place. – Good cleaning: B. cereus spores can stick around in the kitchen. Proper cleaning of equipment, especially if handling a lot of flour, rice, or spices (which can carry the spores), can reduce contamination. For instance, in dairy plants, flushing lines and pasteurizers helps remove spores that might later germinate. – Source control: Use reputable sources for ingredients – e.g., in infant formulas (where B. cereus has been an issue), manufacturers monitor their processes closely to avoid contamination.

These Top 8 harmful bacteria are the ones that cause the most concern in the food industry due to their prevalence, the severity of illness, or both. Each requires somewhat different strategies to control, but you might have noticed a common theme: proper cooking, cooling, storage, and hygiene go a long way in preventing all of these. That’s why food safety rules (whether in a restaurant kitchen or your own kitchen) emphasize things like handwashing, cooking to temperature, not leaving food out, and avoiding cross-contamination. From farm to fork, controlling these bacteria is a continuous effort. Farmers vaccinate chickens against Salmonella, processors pasteurize and test, and food handlers are trained in safe practices – all to keep these microbes at bay.

For anyone in the food industry, understanding these villains is critical. And for everyday folks, knowing about them can inform smarter food handling at home. The good news is that if we respect the basic principles of food safety, we can prevent most foodborne illnesses. The bad news is that it only takes one slip-up in controlling these bacteria for an outbreak to occur. That’s why vigilance is key – the stakes are high when these microbes get into the food supply. By keeping the pressure on these “usual suspects” through good practices, we protect public health and ensure confidence in the food we eat.

References:

- FDA – Get the Facts about Salmonella. (Salmonella causes ~1.35 million illnesses annually in the U.S., second only to norovirus in cases but the leading cause of hospitalizations and deaths from food poisoning.)

- WHO – Salmonella Fact Sheet. (Salmonella is a hardy bacteria that can survive several weeks in a dry environment and several months in water – illustrating its resilience in foods and surfaces.)

- USDA – Clean then Sanitize (Kitchen Cleaning Tips). (Campylobacter can survive on kitchen surfaces for up to 4 hours; Salmonella can last up to 32 hours – highlighting the need for thorough cleaning to remove these pathogens.)

- FDA – Foodborne Illnesses (Organism Chart). (E. coli O157:H7 infection can lead to severe, sometimes life-threatening illness, with symptoms like bloody diarrhea and potential kidney failure, often from undercooked beef or contaminated produce.)

- FDA – Get the Facts about Listeria. (Approximately 1,600 people get listeriosis in the U.S. each year, and about 260 die; the hospitalization rate is 94%, reflecting Listeria’s severity.)

- WHO – Listeriosis Fact Sheet. (Invasive listeriosis in high-risk populations has a high mortality rate of 20-30%, making it one of the most serious foodborne diseases despite its rarity.)

- gov – Prevent Illness from C. perfringens. (Clostridium perfringens is one of the most common causes of food poisoning, causing close to 1 million illnesses in the U.S. every year, often linked to food held at unsafe temperatures.)

- FDA – Foodborne Illnesses (Organism Chart). (Staphylococcus aureus causes food poisoning with sudden onset of severe nausea and vomiting 1-6 hours after eating; typically from unrefrigerated meats, salads, or cream-filled pastries that allowed toxin production.)

- CDC – Chill: Refrigerate Promptly (Food Safety). (Never leave perishable food out more than 2 hours, or 1 hour above 90°F; bacteria in the “Danger Zone” 40-140°F can multiply rapidly, doubling every 20 minutes, which is critical for preventing growth of cereus, C. perfringens, etc.)

- FDA – Foodborne Illnesses (Organism Chart). (Clostridium perfringens causes intense abdominal cramps and diarrhea ~8-16 hours after eating; often from meats, poultry, gravies, or foods that were kept warm for too long – a classic cafeteria outbreak scenario.)